Rethinking Generation & Reasoning Evaluation in Dialogue AI Systems

As Large Language Models (LLMs) gain mass adoption and excitement, there is no shortage of benchmarks within the LLM community; benchmarks like HellaSwag tests for commonsense inference via sentence completion, while TruthfulQA seeks to measure a model’s tendency to reproduce common falsehoods. On the other hand, natural language generation (NLG) evaluation metrics for dialogue systems like ADEM, RUBER, and BERTScore try to capture the appropriateness of responses in mimicking the scoring patterns of human annotators (Zhao et al., 2020).

But as we rely further on (and reap the benefits of) LLMs’ reasoning abilities in AI systems and products, how can we still grasp a sense of how LLMs “think”? Where steerability is concerned — users or developers may desire to add in custom handling logic and instructions — how can ensure that these models continue to follow and reason from these instructions towards a desirable output? There is a sense that verifying the instruction-following thought patterns of these dialogue generations seems to go beyond word overlaps, sentence embeddings, and task-specific benchmarks.

Let’s think beyond LLMs and instead reframe evaluations on an AI system (or agent) level, and examine from first principles on what such a system should and should not do.

Strategy Fulfillment as Steerable Alignment

The fundamental utility of LLMs in commercial applications (or otherwise) is their stellar ability to map input prompts to appropriate output responses. Often, this involves some kind of reasoning procedure, especially ideal for cases where we expect the response to have some degree of variability or flexibility and risk tolerance. For example, say you are a sales representative at company ABC, and you’re using an AI system to read emails from prospects you’ve contacted before, and automatically send out LLM-generated follow-up responses.

Let’s focus on the reasoning step and decompose the task a little. In practice, we separate the prompt into two distinct parts: the user’s query

The task can represented by

where

From the perspective of a developer or service provider,

Back to the email reply generation example, and without loss of generality, let’s say we receive an email from a lead: “I’m interested, can you show me a demo next week?” We can think of our answering strategy

Again, the successful use of LLMs is the notion that they map inputs to appropriate output responses. What does being appropriate entail?

There are two ways to look at this. The first is to gauge how close

The second and more feasible way is to ensure that the LLM-generated response satisfies our strategy since the strategy is where it reasons about the context of the task and how to conditionally behave. We want to find an external evaluator

with sufficiently high accuracy. This evaluator

At the heart of this approach is the fact that we are supervising processes, not just outcomes. Instead of the loosely defined objective of checking if the LLM response answers the user query, we can check that the LLM is “doing the right thing” by conforming to and reasoning about the provided answering strategy since we expect that the strategy provides the best course of action for a given input. Whether or not the strategy itself is chosen correctly (i.e.,

To summarize, regardless of how we implement these instructions (conditional on the query or not), there should be mechanisms to verify that the LLM consistently follows the given instructions.

Catastrophic Generations

Merely fulfilling strategies by the user or system developer is insufficient; we must actively guard against catastrophic generations. User queries may be malicious, or our answering strategies may be ill-specified.

Bad generations throw users off and weaken their trust and confidence in our products or systems. Although this is also domain-dependent, they may take the following form, ordered in increasing order of severity:

- General awkwardness (responses being phrased in an awkward or overly robotic fashion, being overly-apologetic)

- Unnatural verbosity (unexpected level of verbosity or terseness in answering the query)

- Erroneous personalization (mixing up names/profiles/pronouns)

- Implausible responses (illogical responses, stark mismatch in tone, not taking into consideration given obvious contextual cues or nuances)

- Harmful responses (profanities, violence/threats, insults — whether directed to the recipient or third party, egregious unprofessionalism)

Where do we draw the line between a low-quality response and a catastrophic one? It depends on the objective and stakes at hand, but I would posit that the last three can be deemed as “catastrophic”. With erroneous personalization, users may start to doubt the consistency and reliability of the product; for implausible and harmful responses, the AI system ceases to be aligned with human interests, as it fails to embody the fundamental qualities of being helpful, honest, and harmless (Askell et al., 2021).

Notice that bad or catastrophic generations do not depend on the answering strategy or perhaps any improper usage of external information (in retrieval-augmented generation systems), and they should not; we only need to focus on the attributes of the response itself. The reason is simple: it doesn’t matter whether the user sends an inflammatory or malicious query, or if existing prompts fail to provide instructions for such cases — a catastrophic response should never be surfaced to the user.

How can we check for catastrophic generations?

- Erroneous personalization: if “personalization” is used as an explicit strategy as an instruction, we may already be encoding a sort of personalization strategy based on, say, the lead’s profile summary (industry, job title, company, interests, activity history, etc). We can check how the generated output fulfills such a strategy.

- Implausible responses: again, we can call another LLM to critique whether the response makes logical sense, or flows naturally from the query, before sending it out.

- Harmful responses: the OpenAI moderation endpoint is a good place to get started quickly. We might also want to add any domain-specific checks using simple regex checkers or perform thresholding on the similarity between response substrings and known toxic phrases.

Out-of-Distribution Requests

I believe that most of the time, undesirable generations arise from the user queries themselves, be it intentional (like prompt jailbreaking or sending inane requests) or asking a question that the system does not yet know how to handle (

The path for “long-tailed” or OOD queries should always be explicitly handled, with its implementation centered around the product’s UX goals. One can surface the impossibility of handling such a query back to the user (e.g., replying “I don’t understand, can you elaborate further?”), replying with a best-effort generic reply, or even blocking automatically sending out replies until further human intervention.

This alludes to some sort of memory mechanism in AI systems, be it implemented implicitly (via fine-tuning) or explicitly (via external knowledge bases). Ideally, there should be a way for the LLM to know what a normal query looks like, and what queries might not be a good idea for it to handle.

A simple way might be to maintain a list of topics/scenarios and a set of canonical questions for each topic, then classify the query into one of these topic categories via similarity to the canonical questions. If none of them satisfy a similarity threshold, exclude this query in the normal path and handle it separately. To this end, NVIDIA’s NeMo Guardrails is a good place to start for designing such flows. Classical novelty/outlier detection techniques might work well here too.

In summary, monitoring for the accuracy of

Contextual Awareness

It may be worth the effort to explore making full use of the superior, rapidly advancing general reasoning capabilities of LLMs to gradually improve our systems by encouraging higher levels of thought, validating their own hypotheses and building upon their insights, and initiating suggestions for improvement.

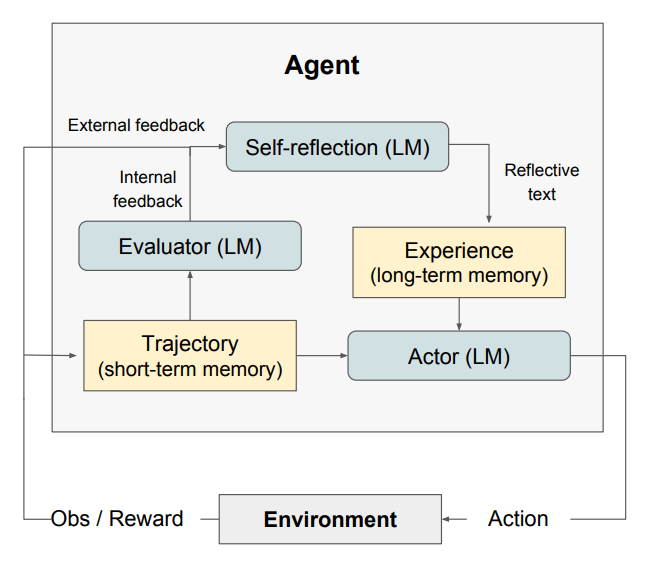

The LLM should have a broad enough context to have a sense of how its generations affect the broader environment. That could mean reflecting on its thought processes (Shinn et al., 2023) (even if they are initially specified by a particular answering strategy) and being able to differentiate between larger objectives and smaller subgoals within the prompt.

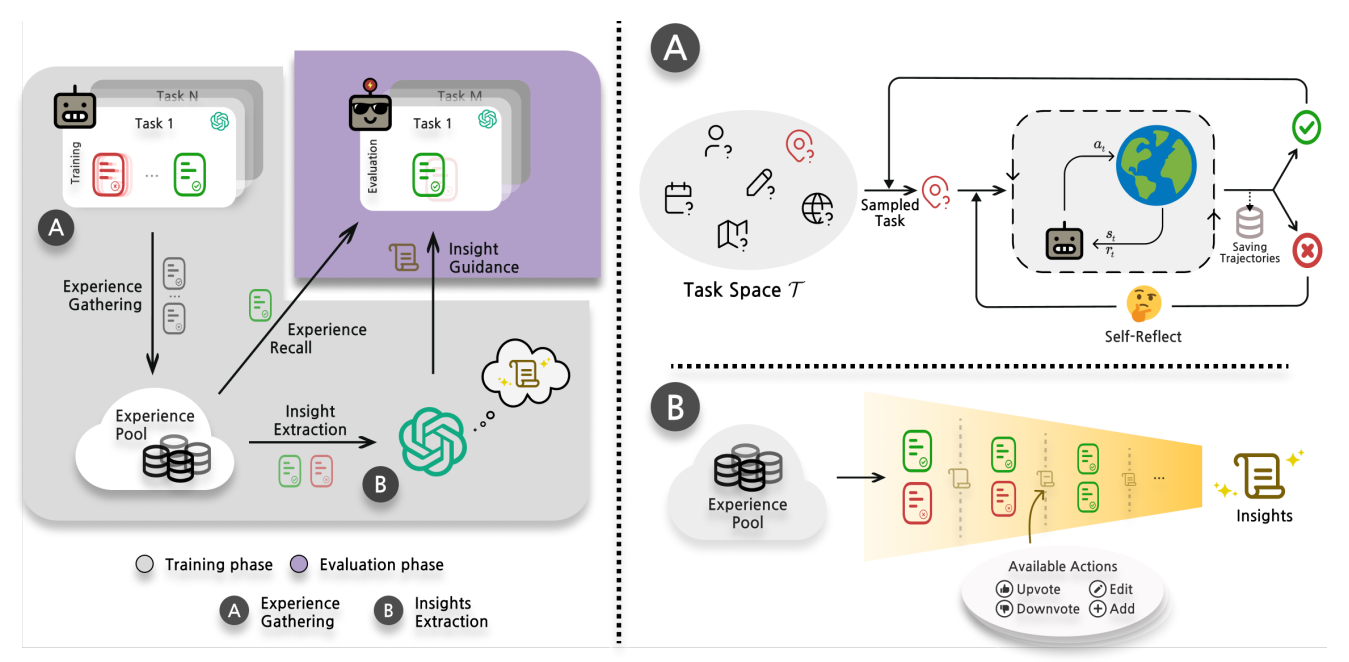

Given a task and some supporting information to perform it, we can encourage an LLM to probe, for example, if there are factual inconsistencies within supporting information, if particular pieces of information could be outdated (if there is data about relative dates), or if the provided information are sufficient to answer the task. The AI system should build up an internal representation of its understanding of how its world works, gradually distilling insights from experiences, and then applying these insights effectively to craft context-aware generations. The ExpeL framework (Zhao et al., 2023) (pictured below) is a good inspiration for an experiential learning framework. In other words, it should formulate an increasingly coherent “Theory of You” as it accumulates experiences.

The next step could be a way to clarify these uncertainties to the system designer (or owner), receive feedback or updated information, and add these back to its memory or insight pool.

Beyond that, an AI system can suggest to the system designer if any answering strategies are lacking in cogency or completeness, whether there are any potential blind spots in its reasoning paths, or if there should be any pieces of information that would let it do its job (fulfilling its main goal) better. Steerability shouldn’t be a one-way street; if LLMs have reached a level of reasoning sophistication, we should let it steer us to some degree and suggest better ways to solve problems.

With this perspective, a way to think about reasoning and generation quality is not just by looking at an LLM’s generations, but also by examining its accumulated insights, and how it synthesizes insights to generate responses. And of course, we should be able to intervene and edit these insights if it is not consistent with our world.

At the time of writing, there is still a distance to go before we reach a state where such systems can be easily deployed, but it is nonetheless interesting to consider.

Closing

As AI systems advance in expressiveness and sophistication, it may be worthwhile to gradually move on from traditional task-specific benchmarks and NLG metrics, and instead reframe these systems as “learning reasoners” and broadly evaluate them as such:

- Are you following the correct process to reach your answer?

- If there are no clear processes to answer the question, what would you do?

- Regardless of the question, don’t ever say anything egregiously inappropriate.

- After having performed multiple variations of a task for some time, what lessons have you learned about it? What insights have you gained about your environment?

Cover image: Wladislaw Sokolowskij (Unsplash)

References

Enjoyed reading this article? More articles you might like to read next: