Building a Fast BPE Tokenizer from Scratch

A Quick Background on Tokenization

Large language models don’t see text - they see sequences of integers. Tokenization is the process of converting text into these integer sequences. The dominant approach is byte-pair encoding (BPE): start with a vocabulary of individual bytes, then iteratively merge the most frequent pairs until you reach a target vocabulary size.

Training a BPE tokenizer on a large corpus is computationally expensive, and a naive implementation on 500MB of text can take hours. In this post, we’ll build five progressively optimized implementations, ultimately achieving a 230x speedup.

We’ll use TinyStories, a dataset of simple children’s stories, as our benchmark corpus. The techniques apply to any text corpus, but TinyStories is small enough to iterate quickly while being large enough to expose performance bottlenecks.

This is a technical deep-dive. We’ll walk through the BPE algorithm, analyze the complexity of each implementation, and show benchmark results. Code is in Python, with an emphasis on algorithmic improvements rather than low-level optimization.

Algorithm & Naive Implementation

BPE was introduced in 1994 by Philip Gage as a data compression algorithm. In 2016, (Sennrich et al., 2016) adapted it for neural machine translation, and it has since become the standard tokenization method for large language models.

The algorithm is remarkably simple. This is Algorithm 1 from Sennrich et al. (2016):

import re, collections

def get_stats(vocab):

pairs = collections.defaultdict(int)

for word, freq in vocab.items():

symbols = word.split()

for i in range(len(symbols)-1):

pairs[symbols[i],symbols[i+1]] += freq

return pairs

def merge_vocab(pair, v_in):

v_out = {}

bigram = re.escape(' '.join(pair))

p = re.compile(r'(?<!\S)' + bigram + r'(?!\S)')

for word in v_in:

w_out = p.sub(''.join(pair), word)

v_out[w_out] = v_in[word]

return v_out

vocab = {'low</w>': 5, 'lower</w>': 2, 'newest</w>':6, 'widest</w>': 3}

num_merges = 10

for i in range(num_merges):

pairs = get_stats(vocab)

best = max(pairs, key=pairs.get)

vocab = merge_vocab(best, vocab)

print(best)

What’s going on here:

-

Pretokenization: The vocabulary is initialized with space-separated characters. Each word ends with a special

</w>marker to distinguish word-final characters (e.g.,tin"newest"vstin"the"). -

Counting pairs:

get_statsiterates over all words, counting how often each adjacent pair of symbols appears (weighted by word frequency). -

Merging:

merge_vocabuses regex to replace all occurrences of the chosen pair with the concatenated symbol. -

Iteration: We repeat until we’ve done

num_mergesmerges.

The key insight is that by iteratively merging the most common pairs, we build a vocabulary that compresses the training corpus efficiently. Common words become single tokens, while rare words are broken into subword pieces.

Byte-Level BPE

Modern implementations operate on bytes rather than characters. This means:

- The base vocabulary is always exactly 256 tokens (one per byte value)

- Any Unicode text can be represented, so there is no “unknown token” problem

- Multi-byte UTF-8 characters are initially split into individual bytes, then merged during training

For example, the Chinese character “你” (U+4F60) is encoded as three bytes: 0xE4 0xBD 0xA0. Initially these are three separate tokens; BPE may learn to merge them.

Also notice that Sennrich et al.’s formulation above uses explicit end-of-word markers (</w>) to handle word boundaries. Modern byte-level BPE (GPT-2 and later) takes a different approach: instead of end-of-word markers, it uses a pretokenization regex (we’ll get into more detail in a bit) that splits text into chunks before applying BPE. Spaces are typically attached to the beginning of words ( the rather than the </w>), and the algorithm operates on raw UTF-8 bytes rather than characters. This eliminates the need for special markers while still respecting word boundaries.

Naive Implementation

Let’s walk through a straightforward Python implementation:

PRE_TOKEN_REGEX = r"""'(?:[sdmt]|ll|ve|re)| ?\p{L}+| ?\p{N}+| ?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+|\s+(?!\S)|\s+"""

def train_bpe_tokenizer(input_path, vocab_size, special_tokens):

# Read the corpus

with open(input_path, encoding="utf-8") as f:

corpus = f.read()

# Initialize vocabulary with all byte values

vocab = {idx: bytes([idx]) for idx in range(256)}

# Pretokenize: split corpus into "words" using regex

word_frequencies = {}

for match in regex.finditer(PRE_TOKEN_REGEX, corpus):

word = match.group()

word_bytes = tuple(word.encode("utf-8"))

word_frequencies[word_bytes] = word_frequencies.get(word_bytes, 0) + 1

# Add special tokens to vocabulary

for i, token in enumerate(special_tokens):

vocab[256 + i] = token.encode("utf-8")

merges = []

num_merges = vocab_size - len(vocab)

for _ in range(num_merges):

# Count all adjacent pairs across all words

pair_frequencies = {}

for word, freq in word_frequencies.items():

for i in range(len(word) - 1):

pair = (word[i], word[i + 1])

pair_frequencies[pair] = pair_frequencies.get(pair, 0) + freq

if not pair_frequencies:

break

# Find the most frequent pair (tie-break lexicographically)

best_pair = max(

pair_frequencies.keys(),

key=lambda p: (pair_frequencies[p], vocab[p[0]], vocab[p[1]])

)

# Create new token

new_id = len(vocab)

vocab[new_id] = vocab[best_pair[0]] + vocab[best_pair[1]]

merges.append((vocab[best_pair[0]], vocab[best_pair[1]]))

# Apply merge to all words

new_word_frequencies = {}

for word, freq in word_frequencies.items():

new_word = []

i = 0

while i < len(word):

if i < len(word) - 1 and (word[i], word[i + 1]) == best_pair:

new_word.append(new_id)

i += 2

else:

new_word.append(word[i])

i += 1

new_word_frequencies[tuple(new_word)] = freq

word_frequencies = new_word_frequencies

return vocab, merges

We use the pretokenization regex pattern from GPT-2 (Radford et al., 2019) to split the corpus before running the BPE.

PRE_TOKEN_REGEX = r"""'(?:[sdmt]|ll|ve|re)| ?\p{L}+| ?\p{N}+| ?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+|\s+(?!\S)|\s+"""

Let’s break this down:

Pattern | Matches | Examples |

|---|---|---|

'(?:[sdmt]|ll|ve|re) | English contractions | 's, 't, 'll, 've, 're |

?\p{L}+ | Optional space + letters | the, hello, über |

?\p{N}+ | Optional space + numbers | 42, 2024 |

?[^\s\p{L}\p{N}]+ | Optional space + punctuation | ..., !!! |

\s+(?!\S)|\s+ | Whitespace runs | trailing spaces, newlines |

Without pretokenization, BPE might merge across word boundaries. For example, it might learn that "e t" (the end of “the” + space + start of “time”) is frequent and create a single token for it. This produces tokens that don’t align with linguistic units.

The regex ensures that words stay intact as merge candidates, spaces are typically attached to the following word ( the not the ), and contractions are handled as separate units.

Complexity Analysis

Let’s define the variables we’ll use throughout this post:

Symbol | Meaning | Typical Value |

|---|---|---|

| Corpus size in bytes | 100 MB – 10 GB | |

| Number of unique words after pretokenization | 100K – 10M | |

| Number of unique adjacent pairs | 50K – 500K | |

| Number of merges (= vocab_size − 256 − num_special_tokens) | 10K – 50K | |

| Average initial word length in tokens | 5 – 10 |

A “word” here means a substring matched by the pretokenization regex - typically actual words, numbers, or punctuation sequences. Note that these values are approximate and interdependent:

Now, let’s trace through one iteration of the merge loop:

Step 1: Count all pairs

for word, freq in word_frequencies.items(): # W iterations

for i in range(len(word) - 1): # L iterations per word

pair_frequencies[pair] += freq

Complexity:

Step 2: Find the best pair

best_pair = max(pair_frequencies.keys(), ...) # P pairs to scan

Complexity:

Step 3: Apply merge to all words

for word, freq in word_frequencies.items(): # W iterations

# Walk through word, merge occurrences # L operations per word

Complexity:

The complexity per merge is

With typical values

Let’s pay closer attention to the merge loop structure:

for _ in range(num_merges): # m iterations

pair_frequencies = {}

for word in word_frequencies: # W words

for i in range(len(word)): # L positions

pair_frequencies[...] += ...

Here lies a critical inefficiency: we recompute all pair frequencies from scratch on every merge!

Notice that when we merge (A, B) -> AB, only these pairs change:

- Pairs containing A or B at the merge positions: frequency increases

- New pairs involving AB: frequency should be zero

All other pairs have their frequencies unchanged. In other words, if the pair (A, B) appears in only 1% of words, we’re doing 100x more work than necessary.

Version 2: Incremental Pair Updates

The fix is straightforward: build the pair frequency table once, then update only what changes after each merge.

Instead of recomputing all pairs, we build the pair frequency table once at the start, and only update the frequencies for affected pairs after each merge.

# Build pair frequency cache once

pair_frequencies = {}

def get_pairs(word):

return [(word[i], word[i + 1]) for i in range(len(word) - 1)]

for word, frequency in word_frequencies.items():

for pair in get_pairs(word):

pair_frequencies[pair] = pair_frequencies.get(pair, 0) + frequency

Now the merge loop only updates what changes:

for _ in range(num_merges):

if not pair_frequencies:

break

# Still O(P) to find the best pair

best_pair = max(

pair_frequencies.keys(),

key=lambda p: (pair_frequencies[p], vocab[p[0]], vocab[p[1]])

)

new_id = len(vocab)

vocab[new_id] = vocab[best_pair[0]] + vocab[best_pair[1]]

merges.append((vocab[best_pair[0]], vocab[best_pair[1]]))

# Only update words that contain the merged pair

new_word_frequencies = {}

for word, frequency in word_frequencies.items():

if best_pair not in get_pairs(word):

# Word is unchanged, just copy it

new_word_frequencies[word] = frequency

else:

# Subtract old pair counts

for pair in get_pairs(word):

pair_frequencies[pair] -= frequency

if pair_frequencies[pair] == 0:

del pair_frequencies[pair]

# Apply the merge

new_word = merge_word(word, best_pair, new_id)

new_word_frequencies[new_word] = frequency

# Add new pair counts

for pair in get_pairs(new_word):

pair_frequencies[pair] = pair_frequencies.get(pair, 0) + frequency

word_frequencies = new_word_frequencies

Complexity Analysis

Initialization (once):

- Count all pairs:

Per merge iteration:

Operation | Complexity |

|---|---|

| Find best pair | |

| Check all words for pair | |

| Update affected words | |

| Total per merge |

where

Wait… we still have

for word, frequency in word_frequencies.items(): # O(W)

if best_pair not in get_pairs(word): # O(L) check

We’re still scanning all words to find which ones contain the pair.

Total:

The asymptotic complexity hasn’t improved! But the constant factors are much better:

- We only rebuild pair frequency entries for affected words

- Dictionary operations are amortized O(1)

In practice, this gives a 5-20x speedup (depending on corpus and vocab size), but we can do much better.

But before we tackle the merge loop bottleneck, let’s grab some low-hanging fruit: pretokenization is parallel and can be optimized independently.

Version 3: Parallel Pretokenization

We know that BPE training has two distinct phases:

- Pretokenization: Split the corpus into words and count frequencies

- Merge loop: Iteratively merge the most frequent pairs

The merge loop is inherently sequential; each merge depends on the previous one. But pretokenization can be parallelized. Each chunk of the corpus can be processed independently.

We can split the corpus into chunks, process each chunk in parallel, then combine the results:

from multiprocessing import Pool

def pretokenize_chunk(chunk, special_tokens):

"""Process one chunk - runs in parallel."""

word_frequencies = {}

for match in regex.finditer(PRE_TOKEN_REGEX, chunk):

word = match.group()

word_bytes = tuple(word.encode("utf-8"))

word_frequencies[word_bytes] = word_frequencies.get(word_bytes, 0) + 1

return word_frequencies

# Split corpus into chunks at document boundaries

def find_chunk_boundaries(file, num_chunks, boundary_token):

file_size = file.seek(0, os.SEEK_END)

chunk_size = file_size // num_chunks

boundaries = [i * chunk_size for i in range(num_chunks + 1)]

# Adjust boundaries to land on special tokens (document boundaries)

for i in range(1, len(boundaries) - 1):

file.seek(boundaries[i])

# Search for next occurrence of boundary token

while True:

chunk = file.read(4096)

pos = chunk.find(boundary_token)

if pos != -1:

boundaries[i] += pos

break

return boundaries

We split at document boundaries (like <|endoftext|>) rather than arbitrary byte positions because splitting mid-stream could break things: we might land in the middle of a multi-byte UTF-8 character (corrupting it), in the middle of a word (causing the regex to tokenize it differently), or in the middle of a special token. By splitting at known document boundaries, each chunk is self-contained and will produce the same word frequencies whether processed alone or as part of the full corpus.

The main training function now looks like this:

def train_bpe_tokenizer_3(input_path, vocab_size, special_tokens, num_processes=None):

if num_processes is None:

num_processes = os.cpu_count()

# Split corpus into chunks

with open(input_path, "rb") as f:

boundaries = find_chunk_boundaries(f, num_processes * 3, b"<|endoftext|>")

chunks = []

for start, end in zip(boundaries[:-1], boundaries[1:]):

f.seek(start)

chunks.append(f.read(end - start).decode("utf-8"))

# Parallel pretokenization

with Pool(num_processes) as pool:

chunk_frequencies = pool.starmap(

pretokenize_chunk,

[(chunk, special_tokens) for chunk in chunks]

)

# Combine word frequencies from all chunks

word_frequencies = {}

for chunk_freq in chunk_frequencies:

for word, freq in chunk_freq.items():

word_frequencies[word] = word_frequencies.get(word, 0) + freq

# Merge loop (same as V2)

...

Complexity Analysis

Pretokenization:

- With p processes:

- Single-threaded was

- Speedup:

Merge loop: Unchanged from V2 -

Total:

Parallel pretokenization is a quick win when we have a large corpus, with multiple cores available to enable parallelism, and when the bottleneck is file I/O. But it doesn’t help when the time taken for the merge loop dominates (i.e., small corpora relative to vocab size)

On a 500MB corpus with 8 cores, pretokenization goes from ~30 seconds to ~5 seconds. But if the merge loop takes 10 minutes, this is a modest improvement.

Now, the merge loop becomes the dominant cost. We’re still scanning all W words per merge to find which ones contain the pair - time to fix that.

Version 4: Inverted Index

The solution is a classic data structure from information retrieval: an inverted index. Instead of scanning all words to find which contain a pair, we maintain a reverse mapping from each pair to the words containing it.

# Forward mapping (what we had before)

words: dict[int, list[int]] # word_id -> list of token ids

word_freqs: dict[int, int] # word_id -> frequency

# Inverted index (new)

pair_to_words: dict[pair, set[int]] # pair -> set of word_ids containing it

When we want to find all words containing pair (A, B), we just look up pair_to_words[(A, B)] -

During initialization, we build both the pair frequencies and the inverted index:

# Convert to ID-based structures for efficient updates

words = {}

word_freqs = {}

for word_id, (word_tuple, freq) in enumerate(word_frequencies_raw.items()):

words[word_id] = list(word_tuple)

word_freqs[word_id] = freq

# Build pair frequencies and inverted index

pair_frequencies = defaultdict(int)

pair_to_words = defaultdict(set)

for wid, tokens in words.items():

freq = word_freqs[wid]

for i in range(len(tokens) - 1):

pair = (tokens[i], tokens[i + 1])

pair_frequencies[pair] += freq

pair_to_words[pair].add(wid)

Now we can directly look up affected words:

for _ in range(num_merges):

if not pair_frequencies:

break

# Still O(P) to find best pair

best_pair = max(

pair_frequencies.keys(),

key=lambda p: (pair_frequencies[p], vocab[p[0]], vocab[p[1]])

)

new_id = len(vocab)

vocab[new_id] = vocab[best_pair[0]] + vocab[best_pair[1]]

merges.append((vocab[best_pair[0]], vocab[best_pair[1]]))

# O(1) lookup instead of O(W) scan!

affected_word_ids = list(pair_to_words.get(best_pair, set()))

for wid in affected_word_ids:

tokens = words[wid]

freq = word_freqs[wid]

# Remove old pair counts from frequencies and index

for i in range(len(tokens) - 1):

p = (tokens[i], tokens[i + 1])

pair_frequencies[p] -= freq

if pair_frequencies[p] <= 0:

del pair_frequencies[p]

pair_to_words[p].discard(wid)

# Apply merge in-place

new_tokens = []

i = 0

while i < len(tokens):

if i < len(tokens) - 1 and (tokens[i], tokens[i + 1]) == best_pair:

new_tokens.append(new_id)

i += 2

else:

new_tokens.append(tokens[i])

i += 1

words[wid] = new_tokens

# Add new pair counts to frequencies and index

for i in range(len(new_tokens) - 1):

p = (new_tokens[i], new_tokens[i + 1])

pair_frequencies[p] += freq

pair_to_words[p].add(wid)

# Clean up the merged pair from index

del pair_to_words[best_pair]

Complexity Analysis

Initialization:

- Build pair frequencies and inverted index:

Per merge iteration:

Operation | V3 | V4 |

|---|---|---|

| Find best pair | ||

| Find affected words | ||

| Update affected words | ||

| Total per merge |

Where

Total:

The key improvement: we replaced

Early merges affect many words—common pairs like (e, d) or (t, h) appear everywhere. But as training progresses, (a) common byte pairs have been merged into larger tokens, (b) remaining pairs are increasingly rare, and (c)

Merge # | Typical A | % of W |

|---|---|---|

| 1-100 | 50,000 | 50% |

| 100-1000 | 10,000 | 10% |

| 1000-5000 | 1,000 | 1% |

| 5000-10000 | 100 | 0.1% |

Bounding Total Affected Words

We can derive a tighter bound on

Observe that each word can only be updated

Therefore:

where

So for V4, the total merge loop work is:

The

Now, it is worth noting that the inverted index uses additional memory:

pair_to_words: dict[pair, set[word_id]]

The inverted index stores at most

On TinyStories (500MB corpus, 10K vocab):

- Without inverted index: ~80 MB

- With inverted index: ~120 MB (+50%)

The memory increase is modest and well worth the speedup.

We still have

Version 5: Heap for Best Pair

A max-heap can give us the maximum element in

Python’s heapq module only provides a min-heap. To simulate a max-heap, we need to:

- Negate frequencies so the smallest (most negative) value corresponds to the highest frequency

- Reverse tie-breaking so the min-heap picks lexicographically larger bytes first (as BPE specifies)

For the tie-breaker, we use a wrapper that reverses byte comparison:

import heapq

class ReversedBytes:

"""Wrapper that reverses comparison order for bytes."""

__slots__ = ('data',)

def __init__(self, data: bytes):

self.data = data

def __lt__(self, other):

return self.data > other.data

def make_heap_entry(pair):

freq = pair_frequencies[pair]

lex = (ReversedBytes(vocab[pair[0]]), ReversedBytes(vocab[pair[1]]))

return (-freq, lex, pair)

heap = [make_heap_entry(p) for p in pair_frequencies]

heapq.heapify(heap) # O(P)

Now the min-heap’s smallest entry corresponds to the pair with highest frequency, with ties broken by lexicographically largest bytes, exactly matching max() behavior.

Handling Stale Entries

When we merge pair (A, B), many pair frequencies change. The heap now contains stale entries:

Heap contains: [(-100, ..., (A, B)), (-95, ..., (C, D)), ...]

After merge: (C, D) now has frequency 80, not 95!

We have three options:

-

Rebuild the heap after every merge:

-

Decrease-key operation: Python’s

heapqdoesn’t support this efficiently - Lazy deletion: Leave stale entries, validate when popping

We’ll use lazy deletion: when we pop an entry, we check if it’s still valid before using it.

# Track which pairs are valid (for lazy deletion)

valid_pairs = set(pair_frequencies.keys())

for _ in range(num_merges):

# Find best valid pair from heap

best_pair = None

while heap:

neg_freq, lex, pair = heapq.heappop(heap)

# Skip if pair was deleted

if pair not in valid_pairs:

continue

# Skip if frequency is stale

current_freq = pair_frequencies.get(pair, 0)

if current_freq != -neg_freq:

# Re-push with updated frequency

if current_freq > 0:

heapq.heappush(heap, make_heap_entry(pair))

continue

# Valid entry found

best_pair = pair

break

if best_pair is None:

break

# Create new token

new_id = len(vocab)

vocab[new_id] = vocab[best_pair[0]] + vocab[best_pair[1]]

merges.append((vocab[best_pair[0]], vocab[best_pair[1]]))

# Update affected words (same as V4)

affected_word_ids = list(pair_to_words.get(best_pair, set()))

for wid in affected_word_ids:

# ... update word, pair_frequencies, pair_to_words ...

# Push new/updated pairs to heap

for p in get_new_pairs(new_word):

heapq.heappush(heap, make_heap_entry(p))

# Mark merged pair as invalid

valid_pairs.discard(best_pair)

But lazy deletion has a cost: stale entries accumulate in the heap. After many merges, there could be a scenario where

len(heap) = 500,000 # Total entries (valid + stale)

len(valid_pairs) = 100,000 # Actual valid pairs

80% of the heap is garbage! This wastes memory and hurts cache performance.

Here, we perform heap compaction by periodically rebuilding the heap to remove stale entries:

# After updating words...

# Heap compaction: rebuild if too many stale entries

if len(heap) > 3 * len(valid_pairs):

heap = [make_heap_entry(p) for p in valid_pairs]

heapq.heapify(heap)

The threshold 3x is tunable: lower (2x) results in more frequent rebuilds but consume less memory, and vice versa.

Complexity Analysis

Per merge iteration:

Operation | V4 | V5 |

|---|---|---|

| Find best pair | ||

| Find affected words | ||

| Update affected words | ||

| Push to heap | — | |

| Total per merge |

*With lazy deletion, multiple pops may be needed. See total work analysis below.

Why does V5 win despite lazy deletion overhead?

A single heappop is

Every heap entry is popped at most once - either as valid (used for a merge) or as stale (discarded). The total entries ever in the heap is:

- Initial entries:

- Entries pushed during merges: each word modification pushes

Since total word modifications across all merges is

- Total entries =

- Total pops ≤ Total entries =

Therefore:

- Total pop work:

- Total push work:

They match, so lazy deletion doesn’t add asymptotic overhead.

Heap compaction:

We compact when len(heap) > 3 x len(valid_pairs). Since total stale entries is

Total complexity:

Recall from V4 that

The first term is initialization; the second is the merge loop (push + pop work).

Unlike V4’s

When Does V5 Win?

Per-merge complexity:

-

V4:

-

V5:

V5 wins when

With typical values

So V5 wins when the merge affects fewer than ~600 words. From our empirical table:

- Early merges (1-100):

- Late merges (5000+):

The crossover depends on where you are in training, not just vocab size. However, since most merges are “late merges” (

In our benchmarks, this crossover happens around vocab_size ≈ 1100-1500: below this, there aren’t enough late merges for V5’s

See below for details.

Benchmarks

To recap, here’s a summary of the complexities for all versions of BPE we’ve seen so far.

Version | Key Optimization | Per-Merge Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | Naive | |

| V2 | Incremental updates | |

| V3 | + Parallel pretokenization | |

| V4 | + Inverted index | |

| V5 | + Heap |

* V1 and V2 have the same asymptotic complexity; V2’s improvement is in constant factors (only rebuilding pair entries for affected words). V3 adds parallel pretokenization but doesn’t change merge loop complexity.

Again, V5’s multiplicative form is counterintuitively faster because its entire cost scales with

Setup

Dataset: TinyStories validation set

Corpus sizes: 1 MB, 5 MB, 10 MB, 21.5 MB

Vocab sizes: 1000, 2000, 5000 (= 744, 1744, 4744 merges)

Machine: Apple M3 Max, 36GB RAM

Python: 3.12, using multiprocessing with 4 workers

Results

For the tables below, entries are duration for the full BPE process in seconds.

Corpus = 1 MB (W=4,658, P=647, L=6.6)

Vocab | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 76.4 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| 2,000 | 162.6 | 10.1 | 9.0 | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| 5,000 | 422.1 | 20.9 | 20.7 | 4.5 | 1.7 |

Corpus = 5 MB (W=8,126, P=796, L=6.8)

Vocab | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 143.3 | 15.8 | 8.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| 2,000 | 305.9 | 24.0 | 17.0 | 4.2 | 2.8 |

| 5,000 | 779.6 | 45.0 | 39.2 | 8.4 | 3.2 |

Corpus = 10 MB (W=10,133, P=856, L=6.9)

Vocab | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 188.4 | 26.3 | 10.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| 2,000 | 400.8 | 37.0 | 22.0 | 5.2 | 3.8 |

| 5,000 | 1001.3 | 65.0 | 51.9 | 10.7 | 4.1 |

Corpus = 21 MB (W=13,109, P=932, L=6.9)

Vocab | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 269.8 | 49.2 | 14.6 | 4.7 | 4.9 |

| 2,000 | 553.8 | 63.9 | 29.2 | 6.9 | 5.3 |

| 5,000 | 1340.9 | 104.9 | 70.6 | 14.0 | 5.8 |

The full results are can be found here.

Key Observations

1. Heap Wins at Large Vocab Sizes

At vocab=5000 (4744 merges), V5 is consistently 2.4-2.6x faster:

Corpus | V4 | V5 | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 MB | 4.5s | 1.7s | 2.6x |

| 5 MB | 8.4s | 3.2s | 2.6x |

| 10 MB | 10.7s | 4.1s | 2.6x |

| 21 MB | 14.0s | 5.8s | 2.4x |

The

This matches our theoretical predictions: V4’s

2. Inverted Index Wins at Small Vocab + Large Corpus

At vocab=1000 with large corpus, V4 edges out V5:

Corpus | V4 | V5 |

|---|---|---|

| 5 MB | 2.6s | 2.6s (tie) |

| 10 MB | 3.3s | 3.4s |

| 21 MB | 4.7s | 4.9s |

With only 744 merges, the heap overhead (wrapper objects, push/pop operations) isn’t amortized.

3. Heap Compaction is Critical

Before implementing heap compaction, V5 used 2x the memory of V4 and often lost at small vocab sizes. After compaction:

Metric | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Memory overhead | 2x | 1.1-1.4x |

| V5 wins at vocab=1000, 1MB? | No | Yes |

The lesson: lazy deletion needs periodic cleanup, or memory bloat kills cache performance.

4. The Crossover Point

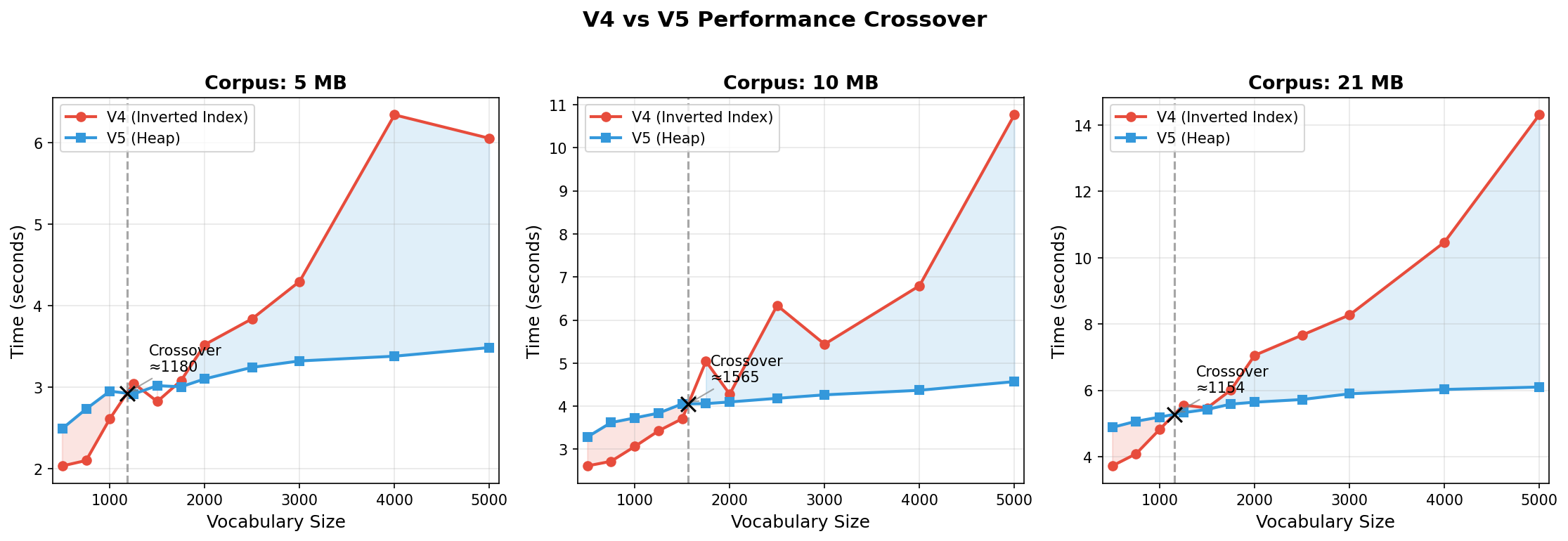

To find the exact crossover point, we benchmark V4 and V5 at fine-grained vocabulary sizes (500, 750, 1000, 1250, 1500, 1750, 2000, 2500, 3000, 400, and 5000) across three corpus sizes (5 MB, 10 MB, 21 MB), interpolating their duration curves to find where they intersect.

- 5 MB corpus: ~1180 vocab size

- 10 MB corpus: ~1565 vocab size

- 21 MB corpus: ~1154 vocab size

- Average: ~1300

The crossover happens earlier than expected—around vocab=1300 rather than 1500. Interestingly, the 10 MB corpus shows a later crossover (1565) than the others. This is likely due to variance in the specific pair distributions: with more unique pairs

Overall Speedup

Comparing V1 (naive) to V5 (fully optimized) on a 21 MB corpus with vocab=5000:

Version | Time | Speedup vs V1 |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | 1341s (22 min) | 1x |

| V2 | 105s | 13x |

| V3 | 71s | 19x |

| V4 | 14.0s | 96x |

| V5 | 5.8s | 231.2x |

The combination of incremental updates, parallel pretokenization, inverted index, and heap yields a ~230x speedup over the naive implementation.

Takeaways

We started with a naive

What Matters Most

For small vocabularies under 2,000 tokens, the inverted index is the main win; heap overhead doesn’t pay off at this scale, making V4 the right choice.

Once you cross into large vocabulary territory (above 5,000 tokens), combining the heap with the inverted index becomes worthwhile. The

For large corpora, parallel pretokenization helps regardless of vocabulary size, and memory becomes the binding constraint, so heap compaction is essential to keep things tractable.

Lessons Learned

1. Profile before optimizing

We expected the heap to always win. It didn’t – at small vocab sizes, the overhead dominated. Only benchmarking revealed the crossover point.

2. Memory matters for performance

Lazy deletion caused 2x memory bloat. The extra memory hurt cache performance so much that V5 was slower than V4 in some cases. Heap compaction fixed this.

3. Asymptotic complexity isn’t everything

V2 has the same

What’s Next?

This implementation handles corpora up to a few GB in reasonable time. For larger scales:

1. Native implementations

HuggingFace’s tokenizers library is written in Rust and runs 10–100x faster than pure Python. It uses the same algorithmic ideas, but eliminates Python object overhead, uses cache-friendly memory layouts, and leverages SIMD for string operations.

2. Distributed training

For web-scale corpora (100GB+), training is distributed across machines. Pretokenization happens in parallel across nodes, pair counts are aggregated, and merge decisions are made centrally.

3. Streaming

Our implementation loads the entire corpus into memory. Streaming approaches process chunks incrementally, trading some accuracy for constant memory usage.

Thanks for reading! If you found this useful, let me know on Twitter/X.

Notes

- The code for all five implementations is available here. This analysis builds on top of the coursework on language modeling from scratch.

- (Zouhar et al., 2023) also analyzed BPE complexity and proposed a similar heap-based optimization. Our analysis uses different notation and provides a more detailed breakdown of each optimization step.

- This GitHub repo also provides an educational walkthrough of efficient BPE tokenization, complete with visualizations.

References

Enjoyed reading this article? More articles you might like to read next: