Learning Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling from 8 Schools

The problem we’re discussing in this post appears in Bayesian Data Analysis, 3rd edition (Gelman et al., 2013). Here, Gelman et al. describe the results of independent experiments to determine the effects of special coaching programs on SAT scores.

There are

| A | 28 | 15 |

| B | 8 | 10 |

| C | -3 | 16 |

| D | 7 | 11 |

| E | -1 | 9 |

| F | 1 | 11 |

| G | 18 | 10 |

| H | 12 | 18 |

From BDA3, we consider that the estimates

Non-Hierarchical Methods

Separate estimates

From the table above, we might suspect that schools tend to have different coaching effects – some schools have rather high estimates (like schools A and G), some have small effects (like schools D and F), and some even have negative effects (schools C and E). But the problem is that the standard errors of these estimated effects are very high. If we treat each school as individual experiments and apply separate normal distributions with these values, we see that all of their 95% posterior intervals overlap substantially.

y <- c(28, 8, -3, 7, -1, 1, 18, 12)

sigma <- c(15, 10, 16, 11, 9, 11, 10, 18)

q_025 <- rep(0, 8)

q_975 <- rep(0, 8)

for (i in 1:8){

q_025[i] <- qnorm(0.025, mean = y[i], sd = sigma[i])

q_975[i] <- qnorm(0.975, mean = y[i], sd = sigma[i])

}

print(cbind(y, sigma, q_025, q_975))

y sigma q_025 q_975

[1,] 28 15 -1.39946 57.39946

[2,] 8 10 -11.59964 27.59964

[3,] -3 16 -34.35942 28.35942

[4,] 7 11 -14.55960 28.55960

[5,] -1 9 -18.63968 16.63968

[6,] 1 11 -20.55960 22.55960

[7,] 18 10 -1.59964 37.59964

[8,] 12 18 -23.27935 47.27935

Pooled estimates

The above overlap based on independent analyses seems to suggests that all experiments might be estimating the same quantity. We can take another approach, and that is to treat the given data as eight random sample under a common normal distribution with known variances. With a noninformative prior, it can be shown that the posterior mean and variance is the inverse weighted average of

cat(paste('Posterior mean:', sum(y/sigma^2)/sum(1/sigma^2)), '\n')

cat(paste('Posterior variance:'), 1/sum(1/sigma^2))

Posterior mean: 7.68561672495604

Posterior variance: 16.58053

The

“The pooled model implies the following statement: ‘the probability is 0.5 that the true effect in A is less than 7.7,’ which, despite the non-significant

Ideally, we want to combine information from all of these eight experiments without assuming the

Bayesian Hierarchical Modeling

We can model this dataset as such: the coaching effect

The vector of parameters

With this setup, we can try to combine the coaching estimates in some way to obtain improved estimates of the true effects

We can write an expression for the unnormalized full posterior density

Next, we can decompose the full posterior density into the conditional posterior,

which will be useful in matching the variance part of the normal densities in this decomposition.

where

and

By forming a quadratic expression in terms of

The posterior mean,

Parameter Estimation

The solution is not yet complete, because

Consider a transformed set of parameters

We can try to get a good estimate of

Now we can write the log posterior as

where the last term comes from the Jacobian.

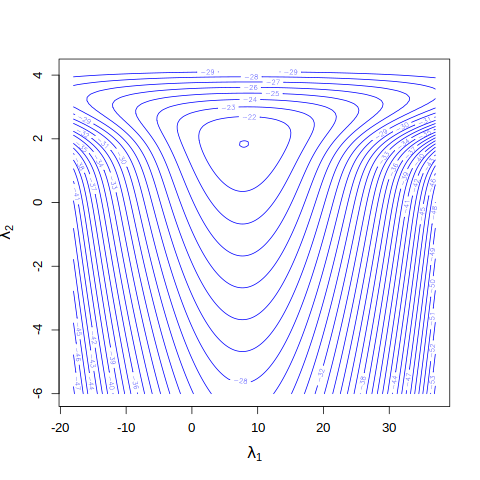

Let’s visualize the log posterior with a contour plot.

# given data

y <- c(28, 8, -3, 7, -1, 1, 18, 12)

sigma <- c(15, 10, 16, 11, 9, 11, 10, 18)

# defining the log posterior for lambda

logpost <- function(lambda, sigma, y){

sum(-0.5*log(exp(2*lambda[2])+sigma^2) -

((lambda[1]-y)^2)/(2*(sigma^2+exp(2*lambda[2])))) +

lambda[2]

}

# grids

lambda_1 <- seq(from = -18, to = 37, by = 0.1)

lambda_2 <- seq(from = -6, to = 4.1, by = 0.1)

z <- matrix(0, nrow = length(lambda_1), ncol = length(lambda_2))

for (i in 1:length(lambda_1)){

for (j in 1:length(lambda_2)){

lambda <- c(lambda_1[i], lambda_2[j])

z[i,j] <- logpost(lambda, sigma, y)

}

}

contour(x = lambda_1, y = lambda_2, z = z, col = "blue", nlevels = 40,

xlab = expression(lambda[1]), ylab = expression(lambda[2]),

cex.axis = 1.1, cex.lab = 1.3)

From the contour plot, the mode seems close to optim() to find the posterior mode and covariance matrix by approximating the log posterior to a (multivariate) normal distribution.

out <- optim(par = c(8, 2), fn = logpost, control = list(fnscale = -1),

hessian = TRUE, sigma = sigma, y = y)

cat('Posterior mode:\n')

print((post_mode <- out$par))

cat('\n')

cat('Covariance matrix: \n')

print((post_cov <- -solve(out$hessian)))

Posterior mode:

[1] 7.926685 1.841525

Covariance matrix:

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 22.3232882 0.1935228

[2,] 0.1935228 0.5352576

The normal approximation to the posterior of

The covariance matrix will be useful when sampling for values of

MCMC Sampling

The Metropolis-Hastings (MH) algorithm is a MCMC method to generate random samples from a density where direct sampling might be difficult (e.g. where normalizing constants are intractable or for high dimensional densities). As this post gets rather lengthy, I shall skip the introduction to the MH algorithm or reserve it for future posts.

Here, we will use MH algorithm to draw 10000 samples. We will use our normal approximation density has the proposal here, as it is the closest to our target posterior density and hence it is more likely to generate accepted samples. The first 5000 samples will be treated as burn-in and discarded; desired samples are obtained after the stationary distribution is reached.

library(LearnBayes)

library(coda)

set.seed(11)

iters <- 10^4

proposal <- list(var = post_cov, scale = 2)

# random walk metropolis

fit1 <- rwmetrop(logpost, proposal, start = post_mode, iters, sigma, y)

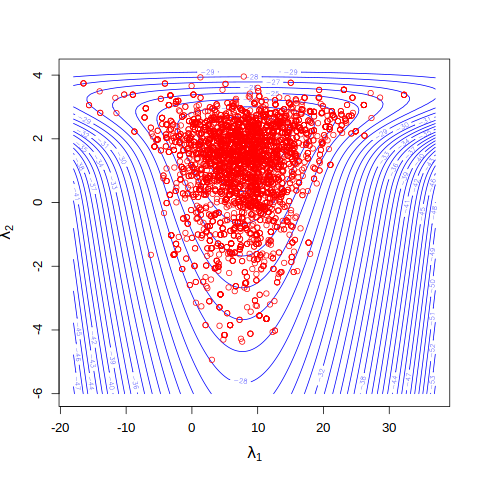

# overlaying last 5000 draws on contour plot of the log posterior

contour(x = lambda_1, y = lambda_2, z = z, col = "blue", nlevels = 40,

xlab = expression(lambda[1]), ylab = expression(lambda[2]),

cex.axis = 1.1, cex.lab = 1.3)

points(x = fit1$par[5001:iters,1], y = fit1$par[5001:iters,2], col = "red")

cat('Acceptance rate: \n')

print(fit1$accept)

Acceptance rate:

[1] 0.3288

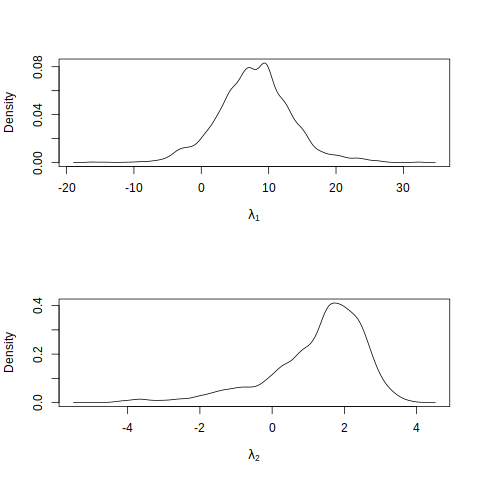

par(mfrow=c(2,1))

plot(density(fit1$par[5001:iters,1]), main = "", xlab = expression(lambda[1]))

plot(density(fit1$par[5001:iters,2]), main = "", xlab = expression(lambda[2]))

The sampling acceptance rate is 32.88%, which is reasonable, and we observe that the MCMC samples

mcmcobj1 <- mcmc(fit1$par[5001:iters,])

colnames(mcmcobj1) <- c("lambda_1", "lambda_2")

par(mfrow=c(2,1))

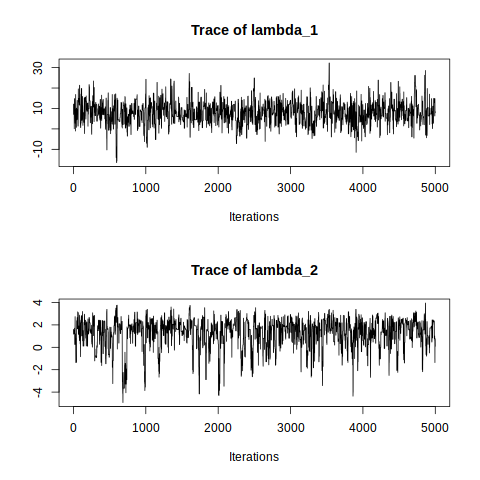

traceplot(mcmcobj1)

The traceplots of both

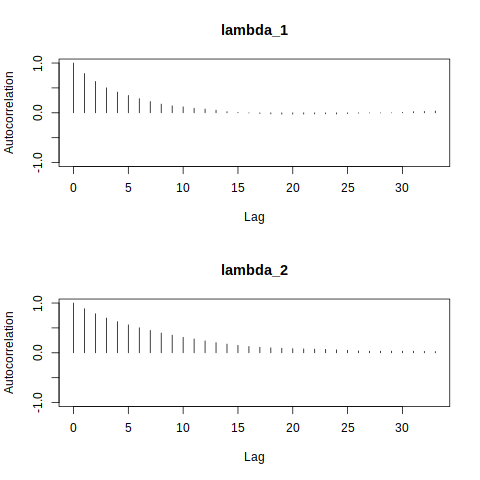

It is also important to analyze the degree of autocorrelation in the sampled values. In an MCMC algorithm like the random-walk Metropolis-Hastings above, the simulated value of

par(mfrow=c(2,1))

autocorr.plot(mcmcobj1, auto.layout = FALSE)

Here, the autocorrelation plots show fast decay in both

With a satisfactory MCMC output analysis, we can use these samples to obtain samples of true effects,

# the last 5000 MCMC samples (lambda_1, lambda_2)

lambda_samples <- fit1$par[5001:iters,]

# function to compute mean

theta_hat <- function(lambda, y_j, sigma_j){

((y_j/sigma_j^2)+(lambda[,1]/exp(2*lambda[,2]))) /

((1/sigma_j^2)+(1/exp(2*lambda[,2])))

}

# function to compute variance

V <- function(lambda, y_j, sigma_j){

1 / (1/sigma_j^2 + 1/exp(2*lambda[,2]))

}

# drawing 5000 samples of theta_j

theta_samples <- function(lambda, y_j, sigma_j){

rnorm(5000, mean = theta_hat(lambda, y_j, sigma_j),

sd = sqrt(V(lambda, y_j, sigma_j)))

}

theta_mean <- rep(0, 8)

theta_sd <- rep(0,8)

# the joint posterior density of (theta_1,...,theta_j)

theta_all <- matrix(0, nrow = 5000, 8)

for (j in 1:8){

thetas <- theta_samples(lambda_samples, y[j], sigma[j])

theta_all[,j] <- thetas

theta_mean[j] <- mean(thetas)

theta_sd[j] <- sd(thetas)

}

print(theta_dist <- cbind(theta_mean, theta_sd))

theta_mean theta_sd

[1,] 11.226786 8.510583

[2,] 7.812253 6.185383

[3,] 6.078697 7.993831

[4,] 7.609353 6.515474

[5,] 5.162853 6.381664

[6,] 6.231208 6.729192

[7,] 10.340858 6.990141

[8,] 8.490497 8.045273

We arrive at estimates of the true coaching effect

Shrinkage

From the conditional posteriors above, we can find that the posterior mean of

where

is the size of the shrinkage of

# shrinkage function for each j

shrink_j <- function(lambda, sigma_j){

(1/exp(lambda[,2]))^2 / ((1/exp(lambda[,2]))^2+1/sigma_j^2)

}

shrink <-rep(0, 8)

for(j in 1:8){

shrink[j] <- mean(shrink_j(lambda_samples, sigma[j]))

}

print(data.frame(school = LETTERS[c(1:8)],

shrink_size = shrink,

rank_shrink =rank(shrink),

rank_sigma = rank(sigma)))

school shrink_size rank_shrink rank_sigma

1 A 0.8328975 6.0 6.0

2 B 0.7376910 2.5 2.5

3 C 0.8458181 7.0 7.0

4 D 0.7620532 4.5 4.5

5 E 0.7096051 1.0 1.0

6 F 0.7620532 4.5 4.5

7 G 0.7376910 2.5 2.5

8 H 0.8676774 8.0 8.0

We observe that shrinkage and sigma values for each school have the same rank. This is consistent with the shrinkage formula above; since the squared inverse of

The samples also provide a way draw other related inferences, such as the probability of seeing an effect as large as 28 for school A, which works out to be a very low value.

sum(theta_all[,1] > 28) / length(theta_all[,1])

0.0468

Note the contrast with the “separate estimates” approach we discussed earlier, which would imply that this probability is 50%, which seems overly large especially given the data from other schools.

We can also ask for the probability that school A has a greater coaching effect than the rest of the schools.

prob <-c()

for(j in 2:8){

prob[j] <-mean(sum(theta_all[,1] > theta_all[,j])) / nrow(theta_all)

}

print(data.frame(school = LETTERS[c(1:8)], probability = prob))

school probability

1 A NA

2 B 0.6346

3 C 0.6800

4 D 0.6382

5 E 0.7162

6 F 0.6804

7 G 0.5382

8 H 0.5994

The probability that school A’s coaching effect is greater than the other schools doesn’t seem that large, even though the original estimates

Conclusion

In summary, Bayesian hierarchical modeling gives us a way to calculate “true effect” sizes that is otherwise hard to obtain (we only have unbiased estimates and standard errors from our dataset). Arguably, the assumptions of both the “separate estimates” and “pooled estimates” approach don’t fully capture the state of our knowledge to be able to use them convincingly. But with the hierarchical model, we now have a “middle ground” of sorts, and it is also flexible enough to incorporate both empirical data and any prior beliefs we might have, both summarized by the posterior distribution. Finally, we can obtain samples using MCMC methods, from which we can perform inferences.

Credits

I learnt of this interesting problem as a piece of assignment from my Bayesian Statistics class, ST4234 in NUS, taught by Prof Li Cheng. I also referred to Bayesian Data Analysis, 3rd edition by Gelman et al for further context and some relevant statistical arguments.

Cover image: Jason Leung (Unsplash)

References

Enjoyed reading this article? More articles you might like to read next: